PhD: Probably a huge Difference

There are very few places in the world with a PhD structure like Denmark – and even fewer with a structure like Aarhus University

There are, in most parts of the world, self-evident truths about getting a PhD.

For example: You must have a Master’s degree before you can get a PhD.

Or: Being a PhD student is not an financial windfall; on the contrary, it will drain you of both time and money.

But the PhD structure in Denmark, at Aarhus University in particular, defies certain conventions. It turns out you don’t need a Master’s degree to be admitted. And as for the money? Well, you’re likely to come out ahead – way ahead.

Mastering the system

Before you can tap into Denmark’s startlingly generous PhD funding structure – more on that in a minute – you must first be accepted into a PhD programme. And this works a little differently at AU than at other universities around Denmark and Europe.

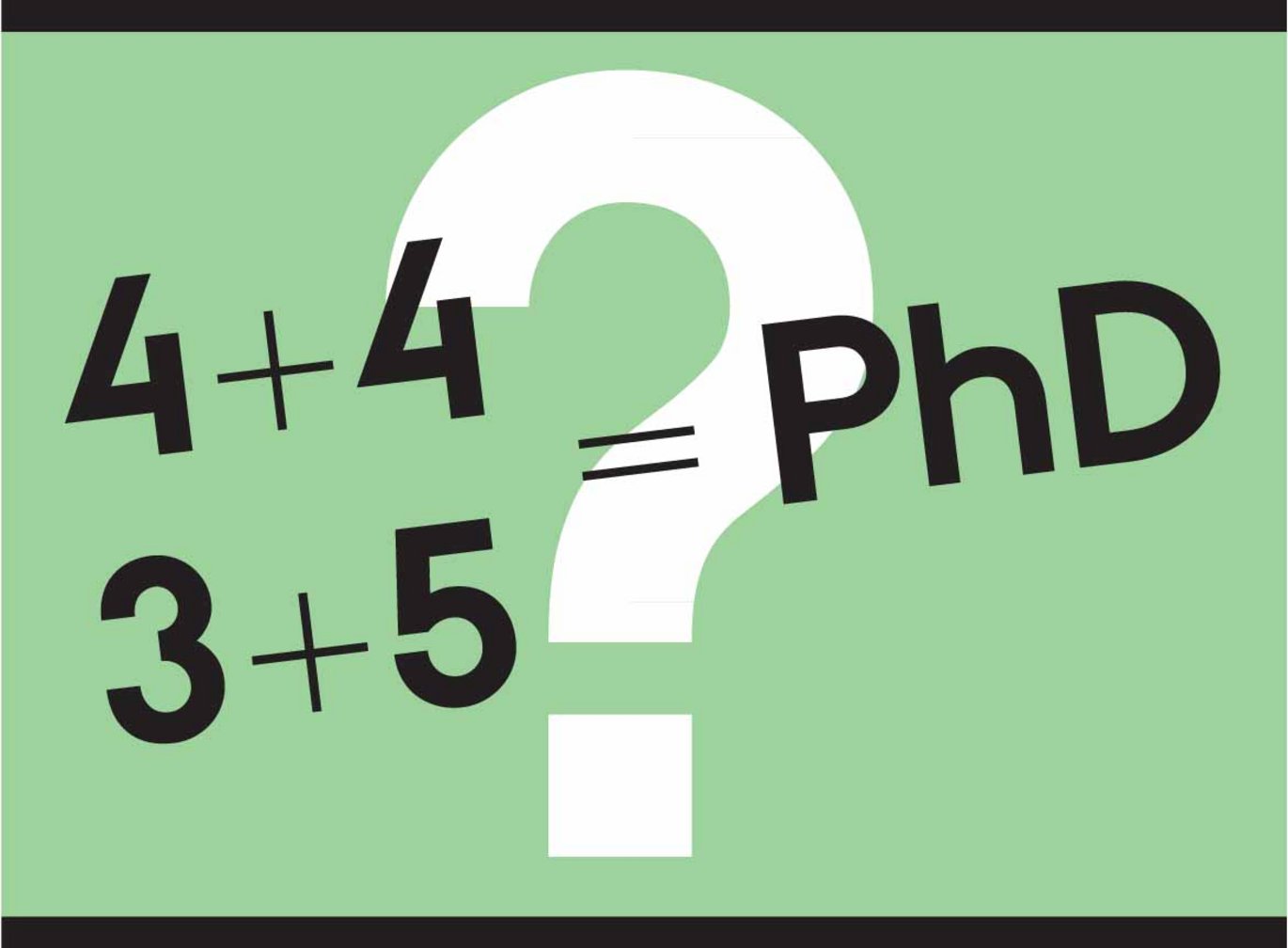

AU employs what’s called the “4+4” system, which requires not a Master’s degree to apply, but some combination of 240 ECTS credits.

“Many students from abroad think that you need to complete your Master’s before applying for a PhD at Aarhus University,” says Morten Kyndrup, Director of the Doctoral School of Arts and Aesthetics. “But that is not the case.”

The 240 credits required of the 4+4 system usually come in the form of a three-year BA programme at 60 ECTS credits per year, plus one year of a Master’s. Students who have completed a four-year BA and one year of a master’s programme are also eligible.

Whatever the combination, “4+4” requires students to have 240 ECTS credits – which typically takes four years – before applying for a PhD programme, which itself would take four years. Hence, 4+4.

Missing in that equation, of course, is a Master’s degree. And therein lies an oddity of the AU system: you don’t need to have completed, or even started, your Master’s degree to gain admittance. It just gets folded into the PhD.

“It’s important to know that you have the chance of registering for the PhD programme before you finish the Master’s degree,” Kyndrup says.

This de-emphasis on the completion of a Master’s started in the Faculty of Science and, four years ago, spread to other faculties, such as Humanities and Social Sciences. The idea was to lure innovative students to AU by allowing access to PhD programmes before the completion of their Master’s degree.

“The advantage is that you get a hold of the talent earlier,” Kyndrup says. “In the old system you had to conclude your M.A. and then apply, and this process often took years. But in this case you sort of go directly into your PhD programme.”

AU also has a “5+3” PhD programme, which requires 300 ECTS credits and an MA prior to application. And in some cases, students may apply for a PhD before they have even started their Master’s degree – the “3+5” or “Bologna Danese” programme. This includes the completion of a Master’s in the first year of the PhD.

DKK for the PhD

Once in the PhD programme, everything is set – at least in terms of money.

According to AU’s website, the 4+4 system pays PhD students nearly DKK 10,000 per month (tuition, by the way, is free). This monthly stipend lasts for two years, at which point the student is employed as a “research fellow” and the money is more than doubled to roughly DKK 25,400, including holiday pay and a pension.

Students in the 5+3 programme receive DKK 25,400 per month for all three years.

For comparison’s sake, DKK 25,400 per month comes out to roughly DKK 300,000 annually, which is more than USD 58,000. According to the United States Census Bureau, the average 2010 income for full-time workers in the U.S. was USD 39,509.

In other words, you can make considerably more money before taxes being enrolled in a Danish PhD programme than by working full-time in America.

“I think some people are surprised by the very high level of financial support – of being hired, of getting a wage, of being treated as a wage-earner,” says Peter Munk Christiansen, a professor of Political Science. “When you talk to foreign students, particularly American PhD students or people from eastern Europe, they find it extremely attractive to come to Denmark.”

Follow the money

According to Guo Wenyong, a PhD student from China, the financial incentives help entice students from all over the world.

“It’s very good because the scholarships give international students a chance to learn here,” says Guo, who arrived at AU in March for the three-year PhD programme in biology. “It’s a good way to get different cultures together.”

The financial assistance applies to post-doctorate researchers as well. England native Chris Sandom, a post-doc researcher at AU who completed his PhD in 2010 at Oxford University, says that while he could have worked in England, the financing opportunities helped lure him to Denmark.

“I worked it out,” Sandom says, “and after tax I reckon I’m still several thousand pounds better off here.” One thousand pounds, by the way, is equal to more than DKK 8,500. “The cost of living is a little bit higher here, but I’m definitely in the black, even if you factor in a few trips home.”